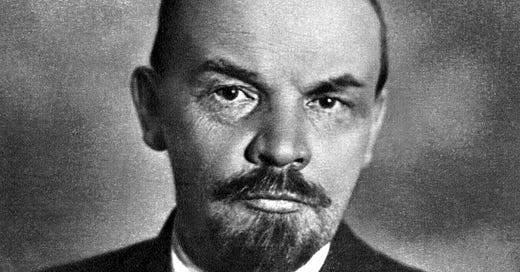

Exactly a century ago, on 21 January 1924, Vladimir Lenin succumbed to the consequences of a third stroke, falling into a coma and dying later that day. Despite only being 53 at the time of his death, Lenin managed to make a devastating impact on the country he ruled. Few today truly understand his legacy and so I asked journalist and recent TRIGGERnome…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Konstantin Kisin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.