The Problem With Adolescence

The conversation about Adolescence, the viral Netflix series about a 13-year-old boy who stabs to death a schoolmate who bullied him on social media, is slowly moving on. I’ve been meaning to write about it for weeks but have struggled to.

For me, the series was hard to watch because my life was shaken very deeply by an episode of violence when I was a young teenager. One otherwise normal day in my early teens, I returned from lessons to my boarding house dorm to find my best friend bleeding from a large stab wound on the right side of his neck. Every time he tried to breathe, the wound would make a horrible gasping sound. Horrified, I rushed to find an adult. By the time we had returned, my friend was gone. After a brief investigation, our geography teacher was arrested and confessed. He’d been sexually abusing my friend and was “forced” to kill him when threatened with exposure.

The reason I’m telling you this is that it’s not true. But human brains only work in one direction. No matter how many times I tell you that this story is false, you can’t change the fact that you saw the horrific images I conjured in your mind. And when you saw them, you felt something. The fact that I immediately recanted the story changes something, but not everything. Negation works in language; it doesn’t work in brains. You can’t unsee the huge pink elephant I just put in your head. The harder you try, the more you fail.

If you feel it was irresponsible of me to lie to you about such a traumatic incident, you’re not wrong. It was. The only reason I did is to illustrate the point: the media, the arts, and entertainment do this to you all the time.

I recall a conversation between my mother and my grandmother in the 1990s. Soap operas were making inroads into the post-Soviet TV market for the first time, and millions of people like my grandmother would be glued to the television, watching terrible Brazilian actors marry, cheat and divorce each other with impressive regularity. My grandmother watched every betrayal, near-death experience, and predictable revelation with the emotional investment of someone watching their only child take their first steps. She howled with rage, gasped in shock, and exhaled with relief in all the right places on the emotional rollercoaster.

My mother seemed irritated by this and would playfully remind my grandmother that what she was watching was fiction. My grandmother’s response was not to argue the facts: “Leave me alone,” she would exclaim, waving my mum’s teasing comments away. Mum was right on the facts, but wrong on the feelings. The possibility that what you’re watching is real is part of the appeal. Securing that suspension of disbelief is the first order of business for a piece of entertainment.

I still remember watching the 2004 movie Crash, which depicts an America being torn apart by bigotry. From rich whites crossing the street to avoid blacks, to racist cops sexually assaulting a black woman in front of her husband after pulling them over for no reason, the film chronicles an interconnected weave of discrimination that ends in tragedy.

Is the film true? Well, every incident in it is statistically almost certain to have happened to someone, somewhere, at some time. But is it representative? Does it leave you with an appropriate perception of the issue? Do you believe that if you showed Crash to 1,000 people and then asked them questions about race relations, their answers would be the same as before they watched it? And do you imagine their perspective would be made more commensurate with the scale of the problem, or less?

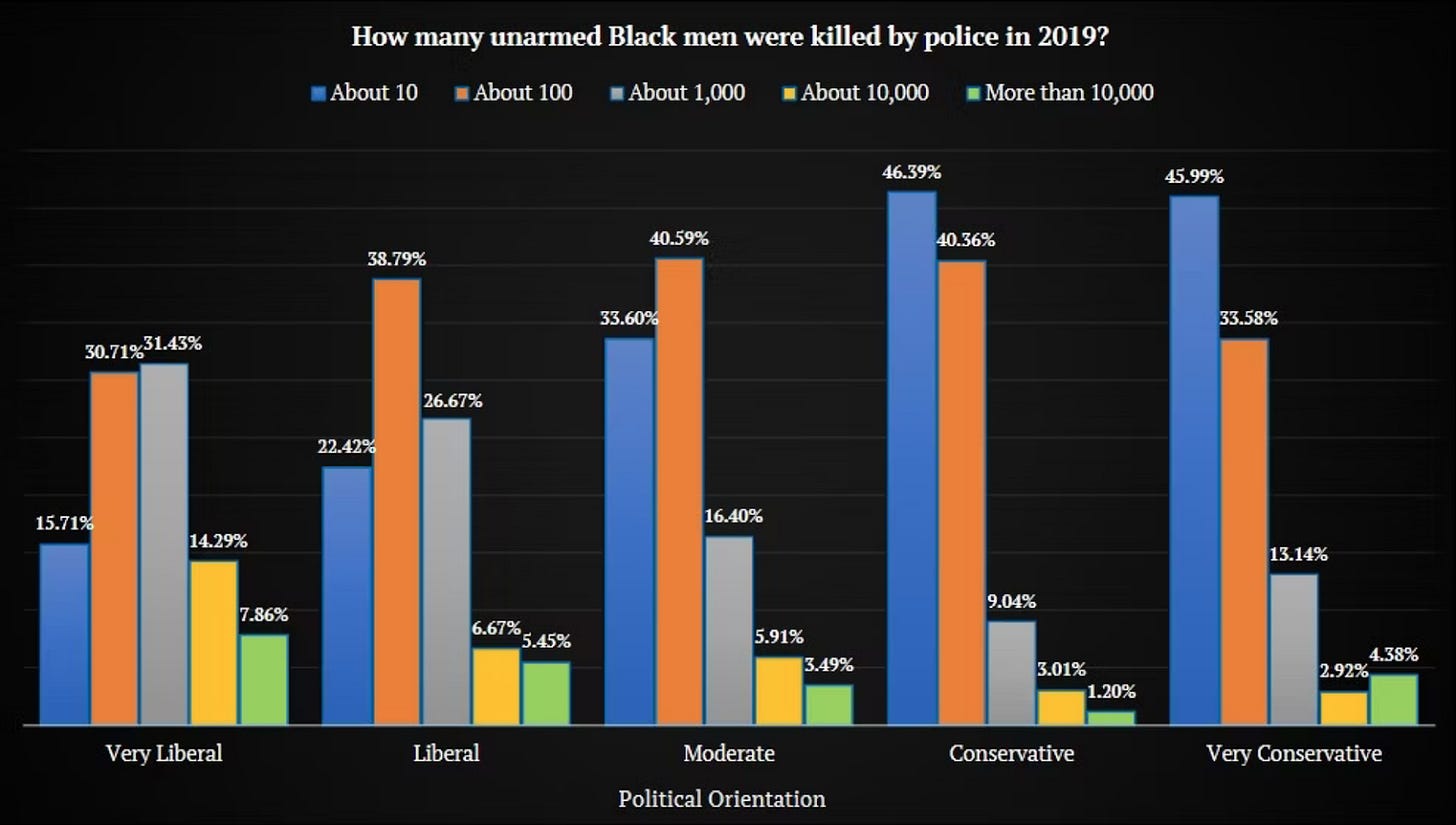

In a 2021 survey, people were asked how many unarmed black men are killed in America every year. Here’s what they said:

The actual number of unarmed black men killed that year was 11. In other words, regardless of political ideology, the majority of Americans exaggerate the scale of the problem by at least a factor of 10—and half of all liberals think 100 times more unarmed black men are killed by the police than actually are. I know these are abstract numbers, so think about it like this: you have $10,000 in the bank. I try to guess how much money you have. My guess is $1,000,000. That’s what’s happening here.

Have you considered buying gold to protect yourself in these uncertain times? My bullion dealer is The Pure Gold Company. Competitive premiums, terrific service. They deliver to the UK, US, Canada and Europe or you can store your gold with them for ease and convenience. (Minimum purchase: £5,000).

Media and entertainment are not the only reasons for this, of course. Most people are not remotely statistically literate. This is why men sometimes dismiss the amount of harassment and inappropriate sexual behaviour women experience. And why man-hating feminists act like all men are predators. The reality is both are making the same mistake. Men who don’t understand what it’s like to be a woman assume that most men are like them and the men they know, so there couldn’t possibly be a real problem with sexual harassment. Angry feminists, meanwhile, don’t understand that their experiences, and those of other women they know, are real but are not being committed by statistically-representative men. Quite the opposite: most crime is committed by a very, very small minority of people who are unrepresentative. So it is perfectly possible that simultaneously, most men are great and most women experience unwelcome advances, lewd comments, and worse.

According to one study, 63% of ALL violent crime in Sweden was committed by just 1% of the population. Whatever the other correlations, the main thing these people have in common is not their race, income, status, or even the fact that almost all of them are men: it’s that they are prepared to be violent in a country where everyone else is not.

But art is powerful precisely because it bypasses the logical brain and hits you in the gut. Not only because emotions are more powerful than reason, but also because art can be beautiful. And like all beauty it can be deceptive. A beautiful person is not necessarily a good person, and beautiful art is not necessarily true.

So where does this leave Adolescence? Well, for a start, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer described this piece of fiction as a “documentary” and wants it shown in schools up and down the country. I can see why. Whatever you think of the message behind it, Adolescence taps into three primal fears that all parents have.